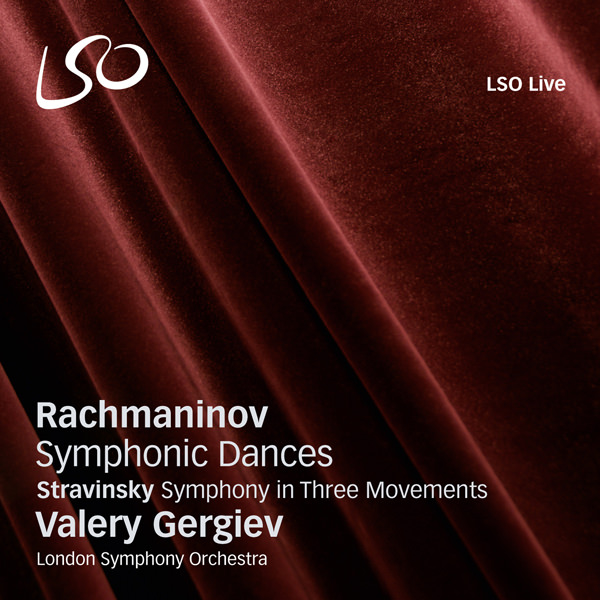

Sergei Rachmaninov – Symphonic Dances / Igor Stravinsky – Symphony in Three Movements – London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev (2012)

DSF Stereo DSD64/2.82MHz | Time – 58:29 minutes | 2,31 GB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download – Source: nativeDSDmusic | Digital Booklet | © LSO

Recorded live 7-8 May 2009 at the Barbican, London

Did Rachmaninov realise that the Symphonic Dances would be his last work? Whether he had such a premonition or not, few composers have ended their careers with such appropriate music, for the Symphonic Dances contain all that is finest in Rachmaninov, representing a compendium of a lifetime’s musical and emotional experience.

The work’s composition was preceded by a big public retrospective of his triple career as composer, pianist and conductor. On 11 August 1939 Rachmaninov gave his last performance in Europe and shortly afterwards left with his family for the US, one of many artists driven from Europe by the approach of war. In the following winter season the Philadelphia Orchestra gave five all-Rachmaninov concerts in New York to mark the 30th anniversary of his American debut (in 1909 he had premièred his Third Piano Concerto in New York, first with Walter Damrosch and then with Gustav Mahler conducting). Rachmaninov appeared as pianist and conductor; the works played included the first three piano concertos, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, the Second and Third Symphonies, the symphonic poem The Isle of the Dead and the choral symphony The Bells.

In the summer of 1941 he wrote to Eugene Ormandy offering him and the Philadelphia Orchestra the first performance of three ‘Fantastic Dances’; when the orchestration was completed two months later, the title had been finalised as ‘Symphonic Dances’. The work exists in two versions: for large orchestra, and for two pianos. Rachmaninov, although an expert orchestrator, was always anxious to have the bowings and articulations of the string parts checked by a professional player, and in this case he enjoyed the assistance of no less a violinist than Fritz Kreisler.

Rachmaninov was usually reluctant to talk about his music, and so we know almost nothing about the background to the composition of the Symphonic Dances. We do know that other of his works owe their existence to some visual or literary stimulus – The Isle of the Dead, for example, or several of the Etudes-tableaux for solo piano – and it is highly likely that the composer invested the Symphonic Dances with a poetic and even autobiographical significance which we can guess at, but which he never divulged. One clue is perhaps provided by the titles which he suggested for each movement. Since Mikhail Fokine had devised a successful ballet using the score of the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (Covent Garden, London, 1939), a further collaboration was now suggested. Rachmaninov played the Symphonic Dances to the choreographer, and explained that they followed the sequence Midday – Twilight – Midnight.

The first dance is a three-part structure, with fast outer sections in C minor enclosing a slower episode in C sharp minor. It is marked by an extraordinary, and at times even eccentric, use of the orchestra. After the stamping opening section, with its use of the piano as an orchestral instrument and piercingly strident woodwind calls, the central section offers gently undulating woodwind lines against which appears a great Rachmaninov melody, given at first to a solo alto saxophone – an eerie, melancholy sound, unique in his music.

Towards the end of this first dance calm spreads over the music, and with a change from C minor to C major comes a broad new theme in the strings against a chiming decoration of flute, piccolo, piano, harp and bells. Rachmaninov would not have expected this to be recognised as a self-quotation, for it is the motto theme of his ill-fated First Symphony, withdrawn (and the score apparently lost) after its disastrous first and only performance in 1897. The failure of this work had been a crippling blow to the young composer, who for some years afterwards had been incapable of further composition. There is no knowing what private significance this quotation now had for Rachmaninov at the end of his life. Was it an exorcism, perhaps, or a recollection of the early love affair that had lain behind the Symphony?

A snarl from the brass opens the second of the dances. This is a symphonic waltz in the tradition of Berlioz, Tchaikovsky and Mahler; and as in movements by those composers, the waltz, that most social and sociable of dances, at times takes on the character of a danse macabre. The title ‘Twilight’ is perfectly suited to this shadowy music, haunted by spectres of the past.

The first four notes of the motto theme from the First Symphony quoted in the first dance have a further significance which reveals itself in the third dance: they form the first notes of the Dies irae plainchant, that spectre of death which haunts so much of Rachmaninov’s music. This third dance is, like the first, in a three-part structure. The central section is imbued with a lingering, fatalistic chromaticism; the outer sections, by contrast, contain some of the most dynamic music Rachmaninov ever wrote. Another significant self-quotation is the appearance of a chant from the Russian Orthodox liturgy, which Rachmaninov had set in his 1915 All-Night Vigil (usually referred to as the Vespers). This chant and the Dies irae engage in what is virtually a life-against-death struggle; and towards the end, at the point where the Dies irae is finally overcome and vanquished by a new liturgical chant, Rachmaninov wrote in the score the word ‘Alliluya’ (Rachmaninov’s spelling, in Latin, not Cyrillic, characters). At the end of his life, then, and with the last music he composed, Rachmaninov seems finally to have exorcised the ghost that stalks through all his music, summed up in the phrase by Pushkin that he had set nearly half a century earlier in his opera Aleko: ‘Against fate there is no protection’.

The first performance was given on 3 January 1942 by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy. The work received a mixed reception, much as the Third Symphony had done five years before. Apart from the hardly relevant question of whether the musical language was too old-fashioned or not, what seems to have confused everyone at the time was an elusive quality to the work, an uncomfortable ambiguity of aims and expression. With the passage of time the Symphonic Dances have gradually come to be recognised as one of Rachmaninov’s finest achievements, where the high level of invention and the orchestral brilliance are only further enhanced by a deep sense of mystery that lies at the heart of the work.

‘The more characteristic a work of Stravinsky, the further it is from the symphonic idea’ wrote Robert Simpson in the long-superseded Pelican guide to the Symphony. Although Simpson may have been rather prescriptive in admitting the Symphony in Three Movements into the canon of 20th-century symphonies, he certainly admired this ‘brilliant and original work’, and he was right in the sense that the young Stravinsky’s attempt to write a well-made symphony under the guidance of his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov – the E flat specimen of 1905-07, his official Opus One – has no individuality at all, while the Symphony in Three Movements is an utterly characteristic and dynamic masterpiece of his maturity. The hybrid origins of the work did, in fact, cause Stravinsky to wonder whether he ought not to have called the result ‘Three Symphonic Movements’. The first movement material, composed in 1942, was originally intended as a dark, tense concerto for orchestra with a role for the piano employed ‘concertante’ style. The piano then bowed out to harp in what became the second movement – sketches for Stravinsky’s unlikely (and swiftly terminated) contribution to Franz Werfel’s film The Song of Bernadette. The finale was completed some time later, before the New York premiere of 1946.

What unites the Symphony in Three Movements is the powering rhythmic intensity which holds the sectional structure together. It is the most insistent since The Rite of Spring over 30 years earlier and it has its roots in Stravinsky’s response to newsreel images of the Second World War which, in an unguarded moment, he specifically attached to certain sections. In the first movement, the timpani’s ‘rumba’ – ‘associated in my imagination with the movements of war machines’, he told Robert Craft – and the spiky shuffling of piano and strings yield to brighter, more lightly-scored sequences; but the ‘war’ element gains the upper hand in insistent, semiquaver figures for clarinet, piano and strings. These in turn lead to full-orchestral explosions which Stravinsky described as ‘instrumental conversations showing the Chinese people scratching and digging in their fields’ before being overrun by scorched-earth tactics. The writing for woodwind that follows is surely a requiem, although thanks to the movement’s uniform tempo, tension never slackens.

Bernadette’s vision, a cantabile flute melody offset by strings and harp, brings a change of air, though there is disquiet in this Andante’s middle section, as well as eloquent writing for string quartet. The brass, silent except for horns here, goose-steps into action near the start of the third movement – an image of military force as graphic as anything in the later symphonies of Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Stravinsky was unequivocal on the imagery of German arrogance, overturned and immobile in the fugue launched by trombone and piano before the Allies fight against the first movement’s ‘rumba’ figure and move on to victory. The composer’s disingenuous claim, ‘in spite of what I have said, the Symphony is not programmatic’ is best interpreted by noting that the description does not account for some of the surprisingly good-humoured invention along the way. It is, then, a symphony with war footage, but nothing as straightforward as a ‘war symphony’. -Andrew Huth & David Nice © 2011

Tracklist:

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Symphonic Dances, Op 45 (1940)

1 Non allegro 12’56’’

2 Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) 9’35’’

3 Lento assai – Allegro vivace – Lento assai. Come prima – Allegro vivace 13’49’’

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Symphony in Three Movements (1942-45)

4 Crotchet = 160 10’07’’

5 Andante – Più mosso – Tempo I 5’45’’

6 Con moto – Più presto – Meno mosso (Con moto) 6’21’’

Personnel:

London Symphony Orchestra

Valery Gergiev, conductor

Download:

mqs.link_RachmaninvSymphnicDancesStravinskySymphnyLSValeryGergiev2012nativeDSDmusicDSD64.part1.rar

mqs.link_RachmaninvSymphnicDancesStravinskySymphnyLSValeryGergiev2012nativeDSDmusicDSD64.part2.rar

mqs.link_RachmaninvSymphnicDancesStravinskySymphnyLSValeryGergiev2012nativeDSDmusicDSD64.part3.rar

![Carl Nielsen - Symphonies Nos. 1-6 - London Symphony Orchestra, Sir Colin Davis (2015) [Blu-Ray Pure Audio Disc + DSF Stereo DSD64/2.82MHz] Carl Nielsen - Symphonies Nos. 1-6 - London Symphony Orchestra, Sir Colin Davis (2015) [Blu-Ray Pure Audio Disc + DSF Stereo DSD64/2.82MHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2015/09/Wnf48VE.jpg)

![Various Artists - The Nordic Sound - 2L audiophile reference recordings (2009) [Blu-Ray Pure Audio Disc] Various Artists - The Nordic Sound - 2L audiophile reference recordings (2009) [Blu-Ray Pure Audio Disc]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2015/12/L2WxB8c.jpg)

![Valery Gergiev - Sommernachtskonzert 2020/Summer Night Concert 2020 (2020) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Valery Gergiev - Sommernachtskonzert 2020/Summer Night Concert 2020 (2020) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2020/12/ssQGLxM.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 3; Balakirev: Russia (2015) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz] London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 3; Balakirev: Russia (2015) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/05/BSou4Lj.jpg)

![Valery Gergiev, London Symphony Orchestra - Mahler : Symphony No. 7 (2020) [FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz] Valery Gergiev, London Symphony Orchestra - Mahler : Symphony No. 7 (2020) [FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2022/09/20/ts4ocld3dgsvb_600.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 1; Balakirev: Tamara (2016) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz + FLAC 24bit/96kHz] London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 1; Balakirev: Tamara (2016) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz + FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/05/YildmwU.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra & Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 2 (2010/2018) [FLAC 24bit/192kHz] London Symphony Orchestra & Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 2 (2010/2018) [FLAC 24bit/192kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2018/10/rWyeYxK.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra & Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphonies Nos. 1-3 - Symphonic Dances (2018) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] London Symphony Orchestra & Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphonies Nos. 1-3 - Symphonic Dances (2018) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2018/10/oEb1W8L.jpg)

![Denis Matsuev, Mariinsky Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov, Stravinsky, Shchedrin: Piano Concertos & Capriccio (2015) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz] Denis Matsuev, Mariinsky Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov, Stravinsky, Shchedrin: Piano Concertos & Capriccio (2015) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/05/9tJtp4v.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Tchaikovsky: Symphonies Nos. 1-3 (2012) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz] London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Tchaikovsky: Symphonies Nos. 1-3 (2012) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/05/5oqqXRM.jpg)

![Sergei Rachmaninov: Symphony No 3 / Mily Balakirev: Russia - London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev (2015) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Sergei Rachmaninov: Symphony No 3 / Mily Balakirev: Russia - London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev (2015) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2016/05/3MBnI0P.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Szymanowski: Symphonies Nos. 3 & 4, Stabat Mater (2013/2018) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Szymanowski: Symphonies Nos. 3 & 4, Stabat Mater (2013/2018) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/06/RuPkwTt.jpg)